Dinu Lipatti continues to be held in high esteem 100 years after his birth due to his recorded legacy. His handful of studio recordings – which his producer Walter Legge said was ‘small in number but of the purest gold’ – and the few concert and test recordings that have been issued since his premature death almost seven decades ago have led to his continually being hailed as one of the all-time great pianists. During his lifetime and since, his records have been best-sellers, with his critically-acclaimed readings of the Schumann Concerto and Chopin Waltzes having rarely been out of print.

It is therefore very disappointing that Warner Classics, who has taken over the EMI catalogue, should have done such a terrible job in commemorating this bestselling artist for the 100th anniversary of his birth. While they have been producing many commendable historical releases of late – including a massive Menuhin Centenary set last year – their Lipatti tribute is thoroughly lacklustre and ill-conceived.

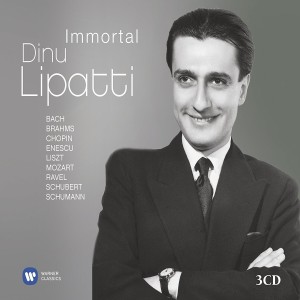

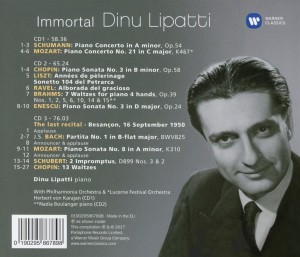

The 7-disc box issued by EMI in 2008 and still produced by Warner includes almost all of Lipatti’s commercial recordings for EMI (absent are his 1947 versions of Chopin’s Waltz Op.34 No.1 and Bach-Hess Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, as well as the Liebeslieder Waltzes, which EMI has never included in a Lipatti set) as well as numerous important concert performances, and is highly recommended for fans of great piano playing. Although this box set is still in the catalogue, Warner decided to produce as an anniversary release a 3-disc compilation entitled Immortal Dinu Lipatti that consists entirely of recordings featured in that set: the Schumann and Mozart Concertos (No.21) with Karajan at the podium, a disc of various solo recordings, and his legendary final recital at the Besançon Festival. Warner’s promotional material speaks to their uninspired approach to producing this tribute – “All three CDs are also in the Icon box dedicated to the pianist (5099920731823) but the Besançon Recital included here benefits from a 24-bit/96kHz remastering made for a Japanese SACD edition in 2011” – thereby acknowledging that they did nothing new for this anniversary, even informing us that this Last Recital disc was remastered 6 years ago… Heaven forbid they should actually remaster any of the recordings again for his centenary celebration!

The Besançon disc does indeed have very good sound and appears to have been gone back to the original INA broadcast source material, as it includes for some reason the spoken announcement of the Mozart Sonata and Schubert Impromptus from the radio broadcast – yet if that source material was used anew, why would they not include the warm-up ‘preluding’ that Lipatti played before the Schubert and Chopin works in the recital? These are present on the master tape and are exquisitely beautiful; it is a mystery why they were never put on LP to begin with, when the arpeggios prior to the Bach and Mozart were, and these would have been most welcome in a new reissue.

Furthermore, the sound on the solo disc of studio recordings is reprehensible. Warner is still using the same transfers of the original 78rpm discs made decades ago – the sloppy side-join in the first movement of the Chopin B Minor Sonata results in a surge in volume midway through the chord that Lipatti played both at the end and beginning of each disc, something evident in every EMI issue of the performance since the 1955 LP set on French Columbia – all these decades the label has been simply tweaking the sound of transfers made over 60 years ago without ever going back to the source material. (APR’s 1999 disc of Lipatti’s 1947 recordings featured the best transfer of the work – Bryan Crimp used freshly stamped vinyl pressings of all the sides for which the original matrices existed.) The Enescu Third Sonata is still issued a semi-tone sharp (in D-Sharp as opposed to D) and the final movement features some computerized distortion that was present in the Icon release and which clearly went unnoticed by the engineers or anyone producing that set and the current release – previous CD and LP incarnations of the performance had no such noise.

Furthermore, the sound on the solo disc of studio recordings is reprehensible. Warner is still using the same transfers of the original 78rpm discs made decades ago – the sloppy side-join in the first movement of the Chopin B Minor Sonata results in a surge in volume midway through the chord that Lipatti played both at the end and beginning of each disc, something evident in every EMI issue of the performance since the 1955 LP set on French Columbia – all these decades the label has been simply tweaking the sound of transfers made over 60 years ago without ever going back to the source material. (APR’s 1999 disc of Lipatti’s 1947 recordings featured the best transfer of the work – Bryan Crimp used freshly stamped vinyl pressings of all the sides for which the original matrices existed.) The Enescu Third Sonata is still issued a semi-tone sharp (in D-Sharp as opposed to D) and the final movement features some computerized distortion that was present in the Icon release and which clearly went unnoticed by the engineers or anyone producing that set and the current release – previous CD and LP incarnations of the performance had no such noise.

Perhaps most reprehensible is a booklet that lacks any written content other than the track listings and recording dates. To produce what is supposed to be a tribute to one of the most revered artists of the 20th century without a single word about the performer, his artistry, and the recordings themselves is lowering the bar to a point that one wonders why Warner even bothered to produce the set. It would have been very easy for them to find a writer – in-house or otherwise – to produce a tribute text, or they might even have simply reproduced a previously published essay (much as they just republished previously produced CDs) … and yet they included nothing. A staggering disappointment, particularly given the fine work Warner has been doing in reissuing historical recordings by the other major artists in their catalogue.

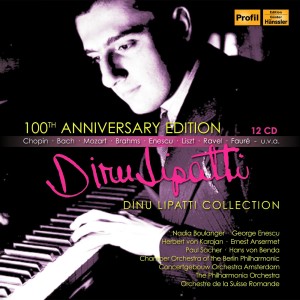

Hänssler in Germany, on the other hand, have produced what is the most comprehensive Lipatti issue produced to date with their 100th Anniversary Edition, including virtually everything of the pianist that’s been available in any format, from his first test recordings in 1936 to his final recorded studio and concert performances, including important items never released on EMI/Warner. They have used all of the material uncovered by my research and featured on the CDs that I co-produced on the Archiphon label in the 90s (though they have done so without seeking authorization), and a little more: I must admit to being a bit surprised that they used the excerpt of an unpublished 1936 test recording of Brahms’ Op.118 No.6 from my YouTube channel – had they written to ask, I could have provided more of the performance (although it is marred by skips in the record in the 1960s tape transfer, the original disc having been lost).

Hänssler in Germany, on the other hand, have produced what is the most comprehensive Lipatti issue produced to date with their 100th Anniversary Edition, including virtually everything of the pianist that’s been available in any format, from his first test recordings in 1936 to his final recorded studio and concert performances, including important items never released on EMI/Warner. They have used all of the material uncovered by my research and featured on the CDs that I co-produced on the Archiphon label in the 90s (though they have done so without seeking authorization), and a little more: I must admit to being a bit surprised that they used the excerpt of an unpublished 1936 test recording of Brahms’ Op.118 No.6 from my YouTube channel – had they written to ask, I could have provided more of the performance (although it is marred by skips in the record in the 1960s tape transfer, the original disc having been lost).

The organizational principle of Hänssler’s set is ideal, presenting Lipatti’s recordings in chronological order across 12 discs, with CD1 being Pre-War Recordings 1936-1938, CDs 2 and 3 War Recordings 1941-1943, CDs 4-7 featuring Post-War Recordings 1945-1948, CDs 8-11 the ‘Last year of Dinu Lipatti 1950’. and CD 12 being the ‘Last Recital o f Dinu Lipatti (age 33)’. Linguistically unidiomatic titles aside, the collection is logically sequenced as a whole, although there are some odd choices throughout: on CD 9, for example, Lipatti’s concert recording of the Mozart C Major Concerto from August 1950 is presented before the February 22 concert performance of the Schumann Concerto, whereas the reverse would have fit the chronological ordering of the entire box set. If they did this in order to present the composers chronologically, then the ordering of solo works on disc 7 is inconsistent, as it features Lipatti’s 1947 Abbey Road recordings of Chopin prior to the two Scarlatti Sonatas recorded the same year, before shifting eras again to Liszt. Lipatti’s 1947 Bach-Hess Jesu Joy was not included on that disc, the producers having chosen to place it at the end of his Besancon recital on the final disc to replicate how Lipatti actually played that recital (a recording of the final portion of his recital that includes the encore has never been found); the only problem is that they have used the 1950 recording and not the 1947 as stated, so that earlier reading is as a result regrettably absent from the set.

f Dinu Lipatti (age 33)’. Linguistically unidiomatic titles aside, the collection is logically sequenced as a whole, although there are some odd choices throughout: on CD 9, for example, Lipatti’s concert recording of the Mozart C Major Concerto from August 1950 is presented before the February 22 concert performance of the Schumann Concerto, whereas the reverse would have fit the chronological ordering of the entire box set. If they did this in order to present the composers chronologically, then the ordering of solo works on disc 7 is inconsistent, as it features Lipatti’s 1947 Abbey Road recordings of Chopin prior to the two Scarlatti Sonatas recorded the same year, before shifting eras again to Liszt. Lipatti’s 1947 Bach-Hess Jesu Joy was not included on that disc, the producers having chosen to place it at the end of his Besancon recital on the final disc to replicate how Lipatti actually played that recital (a recording of the final portion of his recital that includes the encore has never been found); the only problem is that they have used the 1950 recording and not the 1947 as stated, so that earlier reading is as a result regrettably absent from the set.

One of the most unfortunate omissions comes with Lipatti’s 1947 test recordings with cellist Antonio Janigro, never published in his lifetime or by EMI (Walter Legge has a lot to answer for here – his not having released these magnificent performances while claiming to do all he could to promote Lipatti’s art was inexcusable, as the playing of both artists is utterly sublime). Three of the six works that the duo recorded in a Zurich studio are featured, the only takes that were issued on Archiphon in 1995 as we had only located two of the six discs at the time. However, I have since located two of the other works, most notably the first movement of Beethoven’s Third Cello Sonata – obviously of great interest since there are no other known recordings of Lipatti playing Beethoven. If the producers of the set had been in contact to inquire about using the recordings I’d previously discovered or about what else might be available, I would certainly have arranged for them to include these other performances for their first CD appearance. Also missing from the compilation are two previously issued interviews with Lipatti from 1950, although the solo works he played in the radio studio in his July interview are included separately. A third interview made prior to his final concerto performance in Lucerne has still never been published in its entirety.

As regards sound quality, the producers have taken the EMI, Archiphon, Electrocord, and Decca transfers and refiltered them. While there is some better clarity in some works, in others the sound is a bit tinny and processed. They have wisely adjusted the pitch to the 1943 Enescu Third Sonata so that it is on-key (unlike any of the EMI issues) and it sounds very fine indeed, the best commercially available. They have chosen the Archiphon transfer of the Chopin Concerto, which is infinitely better than EMI’s, yet they used the 1995 reissue of the Etude Op.25 No.5 that is missing the first two measures, rather than using the complete version from the 2001 release (from which they took the Concerto). While one might wish for a more robust and less filtered sound in the set, the sound overall is still serviceable and the strength of the compilation certainly makes it a worthwhile purchase.

My final ‘if only’ about the set relates to the booklet, which features a text that is poorly translated into English and occasionally factually incorrect, repeating the famous lie perpetuated by Legge that Lipatti had wanted three or four years to prepare the Tchaikovsky and Beethoven Emperor Concertos, something I disproved in publications starting in 1999 with evidence from EMI’s own archives. The photographs as well appear to have been taken from secondary sources when fine copies would gladly have been provided for this worthwhile project.

All of these reservations aside, the Hänssler release is currently the only way to have access to the widest range of Lipatti recordings in one compilation. The producers deserve kudos for having had the vision to produce this set and for the comprehensive nature of the production. Lipatti fans won’t want to be without it.