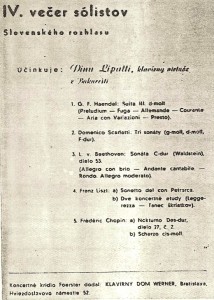

The following is a list of the works that Dinu Lipatti is known to have played in public. It is based on existing concert programs and letters that give evidence that Lipatti actually played these works in concert – his private repertoire was larger. Occasionally, the list – originally compiled by  Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now – lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works – particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! – are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann’s Études Symphoniques, Ravel’s Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin’s Fourth Ballade.

Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now – lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works – particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! – are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann’s Études Symphoniques, Ravel’s Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin’s Fourth Ballade.

It is an enticing list that makes the lack of more recordings by this unique artist all the more regrettable. Let us hope that some other concert broadcasts or private recordings will be found!

Works for Solo Piano and Two Pianos

Albéniz

Iberia, Book 1 – 1. Evocación

Iberia, Book 1 – 2. El Puerto

Iberia, Book 2 – 3. Triana

Navarra (transcribed by Lipatti)

Petite serenade

Andricu

Two Dances

Two Pieces Op.18

Bach

Chorale in G Major, BWV 147 “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” (arr. Hess)

Chorale Prelude, “Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ” BWV 639 (arr. Busoni)

Chorale Prelude, “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland” BWV 659 (arr. Busoni)

English Suite No.3 in G Minor, BWV 808

Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

Pastorale in F Major for organ, BWV 590 (transcribed Lipatti)

Phantasy in A Minor, BWV 904

Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (at least 4)

Prelude and Fugue in E Minor for organ, BWV 533

Siciliano from Flute Sonata, BWV 1031 (arr. Kempff)

Toccata in D Major, BWV 912

Toccata in C Major, BWV 564 (arr. Busoni)

Bartók

Allegro barbaro

Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Mikrokosmos Vol.6)

Sonata for Piano

Beethoven

Piano Sonata No.7 in D Major, Op.10 No.3

Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Op.31 No.2

Piano Sonata No.21 in C Major, Op.53 “Waldstein”

Piano Sonata No.23 in F Minor, Op.57 “Appassionata”

Berkeley

Concert Polka for Two Pianos

Brahms

Capriccio in D minor, Op.116 No.7

Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor, Op.118 No.6

Intermezzo in C Major, Op.119 No.3

Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos

Waltzes Op.39 for Two Pianos (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15 – and perhaps others)

Brero

Five Preludes

Bull

Variations for Keyboard

Byrd

Various Pieces for Keyboard

Casella

Sonatina

Chopin

Ballade No.4 in F Minor, Op.52

Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

Étude in A Minor, Op.10 No.2

Étude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

Étude in C Major, Op.10 No.7

Étude in F Major, Op.10 No.8

Étude in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

Étude in A Minor, Op.25 No.11

Mazurka in E Minor, Op.41 No.1

Mazurka in B Major, Op.41 No.2

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.41 No.4

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

Polonaise in E-Flat Major, Op.22

Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor, Op.44

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op.61

various Preludes Op.28 (at least 6)

Rondo in F Major, Op.5

Scherzo No.1 in B Minor, Op.20

Scherzo No.3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.39

Scherzo No.4 in E Major, Op.54

Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

Waltzes Nos.1 through 14

Waltz Op. Posth (which one is unknown)

Debussy

Arabesque (No.1 or 2)

Estampes No.2, “La soiree dans Grenade”

Étude pour les arpèges composés (and possibly others)

L’isle joyeuse

Images Book 1 No.1: “Reflets dans l’eau”

Images Book 1 No.2: “Hommage a Rameau”

Preludes (various)

Dohnányi

Capriccio in F Minor, Op.28 No.6

Enescu

Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op.24 No.1

Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24 No.3

Suite No.2 in D Major, Op.10

Variations on an Original Theme for two pianos, Op.5

De Falla

Ritual Fire Dance

Fauré

Impromptu No.3 in A-Flat Major, Op.34

Nocturne No.1 in E-Flat Minor, Op.33

Françaix

Concertino for two pianos

Handel

Suite No.3 in D Minor, HWV 428

Jora

Jewish March Op.8

Klepper

Two Dances

Lazar

Two Bagatelles

Lipatti

Compositions of childhood

Romanian Dances for two pianos

Three Dances for two pianos

Nocturne

Phantasie for piano solo

Sonatina for left hand

Suite for two pianos

Liszt

Concert Etude, “La Leggierezza”, S.144

Concert Etude, “Gnomenreigen”, S.145

Harmonies du soir

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

Mihalovici

Deux pieces impromptues, Op.19

Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 8 in A Minor, K.310

Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K.448

Mozart-Busoni

Duettino concertante for two pianos

Negrea

Sonatine Op.8

Nottara

Two Dances

Poulenc

Six Nocturnes

Ravel

Miroirs No.4, “Alborada del gracioso”

Miroirs No.5, “La vallee des cloches”

Le tombeau de Couperin

La Valse for two pianos

Scarlatti

Piano Sonata in E Major, L.23

Piano Sonata in G Major, L.387

Piano Sonata in D Minor, L.413

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major

Piano Sonata in F Major

Piano Sonata in G Minor

Schubert

Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

Piano Sonata No.21 in B-Flat Major, D.960

Allegro in A Minor for two pianos, D.947

Schumann

Blumenstück, Op.19

Carnaval, Op.9

Études Symphoniques, Op.13

Novelette No.2 in D Major, Op.21

Stravinsky

Danse russe (from “Petrouchka”)

Sonata for piano

Weber-Corder

Invitation to the Dance for two pianos